català

español

english

français

Archaeology and political and cultural Catalanism

The origins of an exceptional decade, 1907-1914

World War 1, Mancommunity, IEC and Pere Bosch Gimpera

1915. A first attempt at professionalization

Catalan archaeology’s prodigious decade

Catalan archaeology in and beyond Catalonia

The great adventure in Baix Aragó

The Balearic and Pityuses Islands: the personal project of J. Colominas

The final agony of a prodigious decade

Catalan archaeology’s prodigious decade

The starting point for the golden age of Catalan archaeology in the years before the Spanish Civil War of 1936–1939 can be traced back to the beginning of the exploration and excavation campaigns in Baix Aragó. At least until 1920, this was one of the two great projects undertaken by Catalan archaeologists under the auspices of the Institute of Catalan Studies. The other was the huge task of excavating the pre- and the protohistorical sites of the Catalan-speaking Balearic and Pityuses Islands. To these major projects, we can add a third — the excavation of the ruins of Empúries from 1908 onwards carried out under the supervision of the Barcelona Museums Board.

Method, method and more method

Bosch Gimpera immediately surrounded himself with a magnificent team of workers that combined experienced as well as relatively less practiced archaeologists. The team continued to grow in number and in specialization, and included archaeologists such as Emili Gandia, Josep Colominas, Matias Pallarés, Lorenzo Pérez-Temprado, Agustí Duran i Sanpere, Joaquim Folch i Torras, Lluís Pericot, Josep de Calassanç Serra-Ràfols, Albert del Castillo and Josep Gudiol i Ricart, amongst others.

In fact, this period coincided with a generational change that spanned the 19th and 20th centuries. All the archaeologists shared a number of characteristics and objectives that were embodied in their unbounded enthusiasm for this new project, part of a new scientific archaeological discipline whose methods would provide many new pieces for the country’s museums, as well as a framework for the scientific description of the pre- and protohistory of Catalonia within the triple context of the Iberian Peninsula, Europe and the Mediterranean.

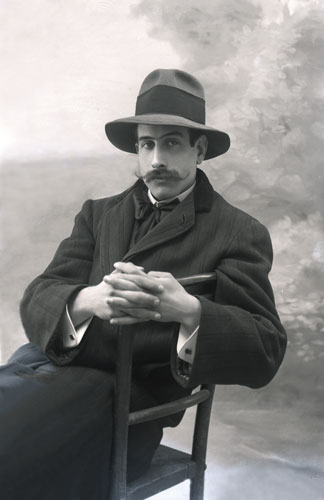

Josep Colominas Roca (1883-1958).

MAC Archive.

Colominas Collection.

Agustí Duran i Sanpere (1887-1975), on the right.

La Segarra County Archive.

Duran i Sanpere Collection.

Francesc Martorell Trabal (1887-1935), secretary of the Historical-Archaeological Section.

IEC Archive.

First of all, Catalan prehistory, the great unknown

On 4 January 1915 Bosch Gimpera was in the process of drawing up an inventory of all the known prehistorical sites in Catalonia, which he submitted for consideration in 1916 for the Historical-Archaeological Section’s awards. However, it was not admitted as it had been written on the basis of the research, although original, that had been funded by the IEC. The interest in prehistory and the stimulus provided by the excavations of Marià Vidal encouraged the IEC in the period 1915–1920 to undertake digs in many Catalan caves with archaeological remains, including Joan d’Os (Tartareu), Solanes (Caldes de Montbui), Can Pasqual (Castellví de la Marca), Fonda (Salomó) and Can Sant Vicenç (Sant Julià de Ramis), amongst others.

At the same time, Bosch Gimpera and Josep Colominas were excavating the necropolis of Can Missert (Terrassa) and Matias Pallarés was working in the cave at Sant Julià de Ramis. In 1917, excavations were undertaken at Can Roqueta, Can Bon Vilà and Can Barba (El Vallès Occidental), while in 1923 IEC carried out one of its most prestigious excavations in the Pyrenees in the cave at La Fou de Bor (La Cerdanya) — all this without ever neglecting the dolmens in Alt and Baix Empordà, Osona, El Maresme and the Pyrenees.

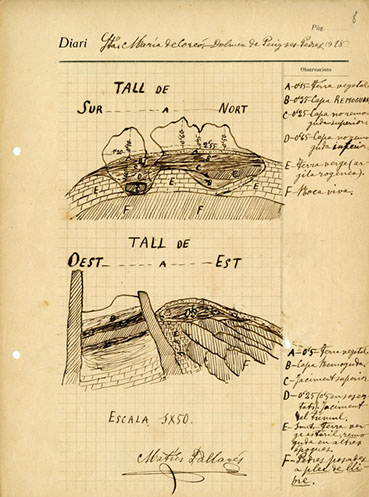

Stratigraphic cross-section taken from the diaries kept by the Institute of Catalan Studies of the excavation of the dolmen of Puig Ses Pedres, at Santa Maria del Corcó. 1918.

MAC Archive.

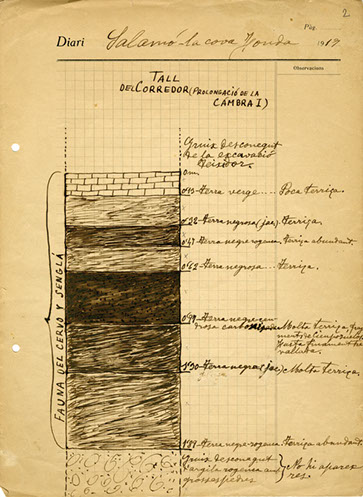

Stratigraphic cross-section taken from the excavation diaries of the digs carried out by the Institute of Catalan Studies in Cova Fonda (Salomó). 1917.

MAC Archive.

The dolmen at Can Roquet, known as La Roca d'en Toni (Vilassar de Dalt, Barcelona). 1917.

MAC Photographic Archive.

Two pottery vases from sepulchres 3 and 4 at the moment of discovery. Can Missert (Terrassa).

MAC Photographic Archive.

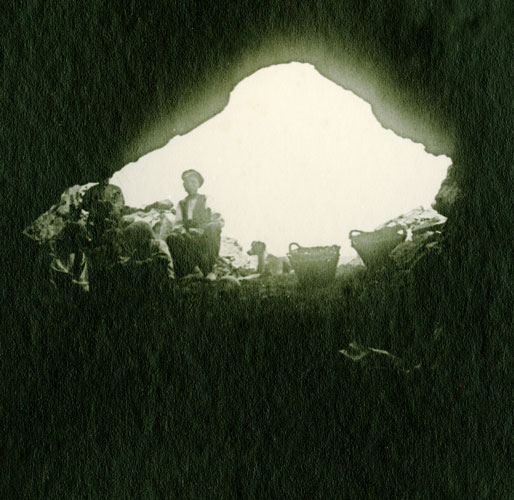

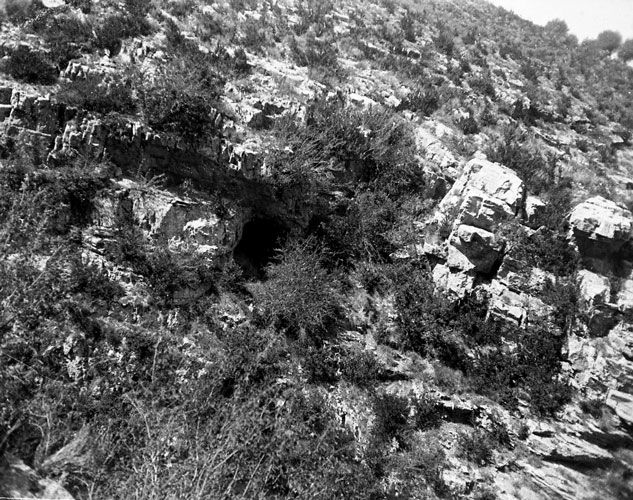

View from the inside of the entrance to Cova de Joan d'Os (Tartareu, Lleida). 1916.

MAC Photographic Archive.

Cova de la Fou (Bor, Cerdanya). July–August 1923.

MAC Photographic Archive.

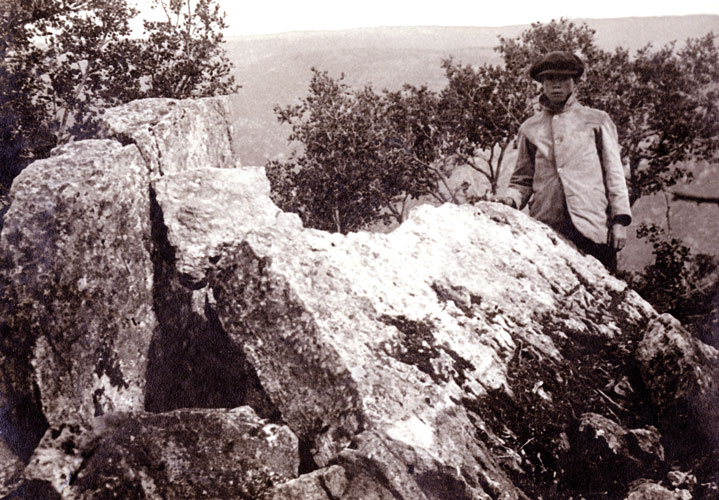

Dolmen of Mas del Boix (El Brull, Aiguafreda). May 1916.

MAC Photographic Archive.

Pere Bosch Gimpera at the dolmen of Puig Ses Lloses (Folgueroles). May 1916.

MAC Photographic Archive.

Pit-grave at Bòbila Boatella. Vilassar de Dalt.

MAC Photographic Archive.

The contribution to the study of Levantine cave art

The discovery of Cova dels Moros near El Cogul in 1908 provided a huge stimulus for the study of Levantine cave art in Catalonia. The scope of this art, first discovered in 1903 at Roca dels Moros de Calapatà (Cretes, Baix Aragó), was extended enormously with the discovery in 1917 of the paintings in El Barranc de la Valltorta (Tírig/Albocàsser, Castelló). The IEC immediately sent a group of experts (March 1917) and in May of that year, Josep Colominas, accompanied by the artist Joan Vila i Pujol (whose artistic name was D’Ivori), explored the valley (at the same time as he excavated Cova dels Melons) and made tracings of the paintings in Cova dels Melons, Cova dels Cavalls and Cova de la Saltadora. Subsequently, in 1921, local people from Tivissa revealed the existence of other groups of cave paintings.

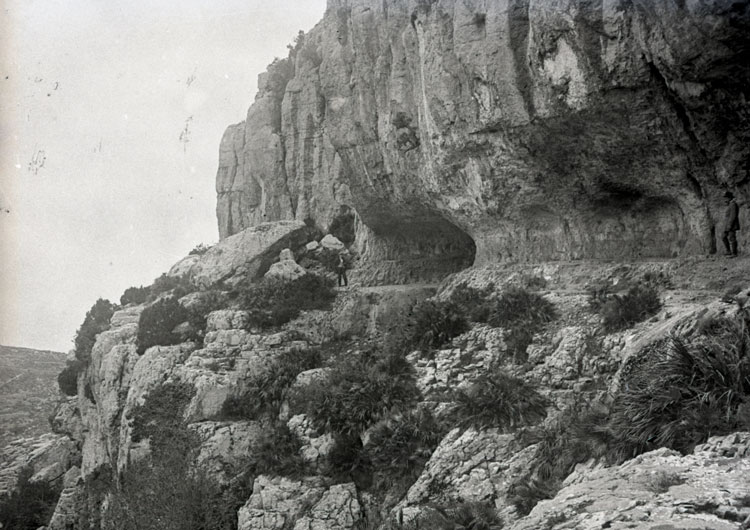

Abric (a shallow cave) of La Roca dels Moros in the Barranc de Calapatà (Cretes, Terol). 1915.

MAC Photographic Archive.

Abric (a shallow cave) of La Roca dels Moros (El Cogul).

MAC Photographic Archive

Cova del Ramat (Tivissa). 1922.

MAC Photographic Archive.

La cova del Civil (Tírig, la Valltorta). 1917.

MAC Photographic Archive.

Cova Gran del Puntal (la Valltorta). 1917.

MAC Photographic Archive.

Water colour depicting human figures from Cova de la Saltadora (La Valltorta), painted by Joan Vila in 1917.

MAC Archive.

Room nº 10 with mosaics from the Roman villa of Els Ametllers (Tossa de Mar). 1921.

MAC Photographic Archive.

Contacts throughout the country

The whole of the Excavations Service team continued to receive a steady flow of information from a widespread network of enthusiasts and less knowledgeable local people; a good example of the latter was the discovery communicated to the Service in 1916 by someone from the town of Sant Feliu de Codines of the prehistorical remains in Cova de Solanes.

Some like Doctor Ignasi Melé, the discoverer and excavator of the villa of Els Ametllers de Tossa, which was eventually purchased by the IEC in 1923, provided information on a very regular basis.

Doctor Ignasi Melé (seated with hat) in the Roman villa of Els Ametllers de Tossa.

Centre of Tossa Studies.

Tossa Municipal Archive.

The influence of classical archaeology

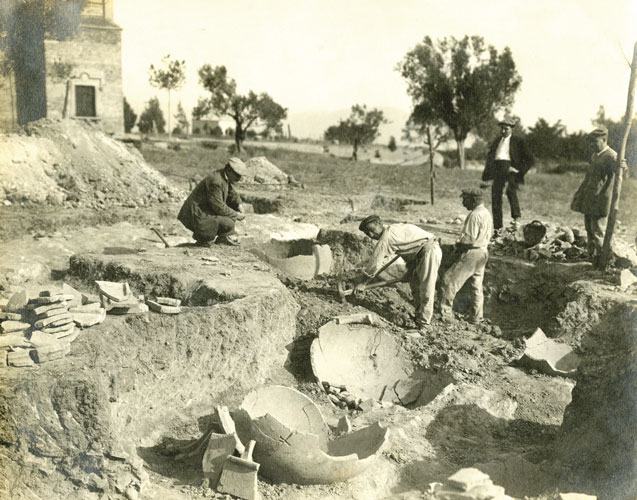

Puig i Cadafalch was a greater advocate of classical archaeology. Despite his numerous commitments elsewhere, he remained at the fore of the excavations at Empúries, where work continued every year thanks to the efforts of Emili Gandia. Puig i Cadafalch was involved in the study of other Roman remains. In 1916 he negotiated with the Archbishop of Tarragona the beginning of excavations at the foot of the city’s walls. In 1917 he supervised the excavations in the villa of La Salut in Sabadell carried out by the painter Joan Vila Cinca. In 1918 he promoted the construction of a large-scale model of the excavations at Empúries. Finally, in 1923 he took the decision to begin digging at La Fàbrica de Tabacs in Tarragona, where an important palaeo-Christian necropolis was eventually unearthed.

Aerial photograph of Empúries. 1926.

MAC Archive.

Emili Gandia Collection.

Archaeological excavations of a dolium in sector C. Near El Santuari de la Salut (Sabadell). 1914.

MAC Photographic Archive.

Pedestal found during the excavations of the foundations of the Fàbrica de Tabacs in Tarragona. Seated, Josep Colominas. 1924.

MAC Photographic Archive.

Tarragona. Excavations of the Roman Theatre in Tarragona. Discovery of the sculpture ‘Thoracata’. July–October 1919.

MAC Photographic Archive.

Finding of a fragment of a torso of a sculpture. Excavations of the Roman Theatre in Tarragona (Tarragona). September and October 1919.

MAC Photographic Archive.

Discovery of a mosaic during the excavations of the Roman villa at Vilagrassa (L’Urgell). November 1927.

MAC Photographic Archive.

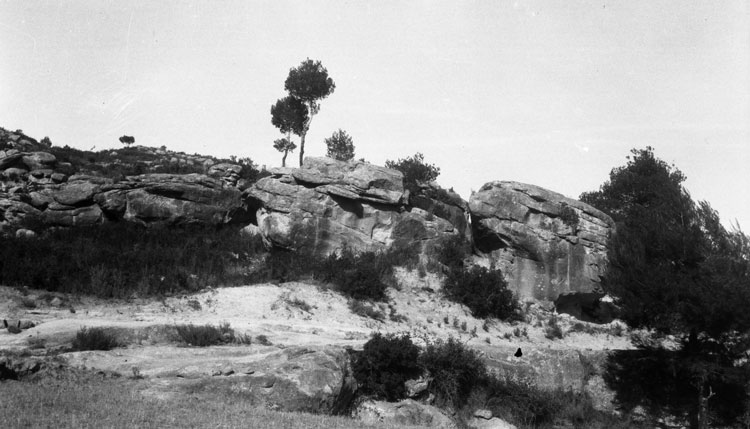

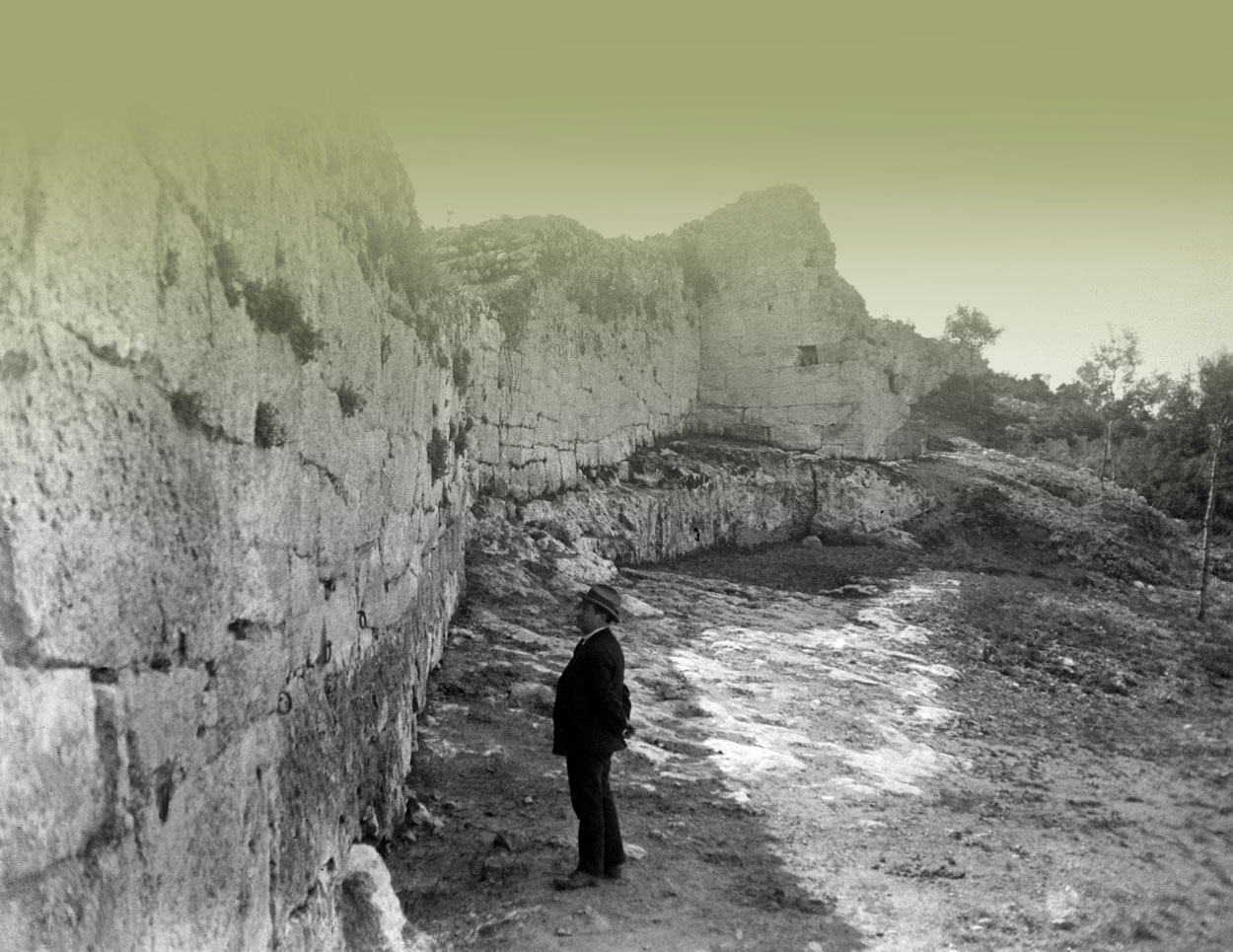

Exterior of the wall surrounding the Olèrdola complex. Between 1915 and 1920.

MAC Photographic Archive.